Functional Equivalence Revisited: Legal Translation in Persian and English through Parallel Corpus

1. Introduction

Researchers have described legal translation as a category in its own right (Garzone, 2000). This is mainly due to the complexity of legal discourse that combines two extremes: the resourcefulness of the literary language used for the interpretation of ambiguous meanings and the terminological precision of specialised translation. The translation of legal texts require particular attention because it ‘consists primarily of abstract terms deeply and firmly rooted in the domestic culture and intellectual tradition’ (Chromá, 2004) and thus entails a transfer between two different legal systems, each with its own unique system of referencing.

According to Šarčević (2000):

‘…law remains first and foremost a national phenomenon. Each national or municipal law… constitutes an independent legal system with its own terminological apparatus and underlying conceptual structure, its own rules of classifications, sources of law, methodological approaches, and socio-economic principles.’

This means that in order to translate the terminology of official written in different legal traditions accurately it is necessary to understand those traditions since the main challenge of the legal translator is the incongruence of legal systems’. Alcaraz and Hughes (2002) add that the translatability of legal texts depends directly on the relatedness of the legal systems involved in the translation. The Persian legal system is based on Islamic law, i.e. on civil law, and has a civil code, the Civil Code of Persia. The United Kingdom does not have a "written" constitution and its law is made up of four main parts: statute law, common law, conventions and works of authority. Common law that consists of rules based on common customs and on judicial decisions has therefore very little ‘relatedness’ to Persian civil law that is created by statue (Shiravi, 2004).

Persian, English history and tradition have also little in common and thus the languages of law have been subject to very different influences. English legal terms have their roots in Latin, French and Norman, Greek, Anglo-Saxon and English traditions. Persian terminology originates from Arabic mainly from Islam with some impact from the annexations Persia by Arabs during Caliphs epoch. The vast differences in the histories of Persian and English law and the associated incongruity of terminology highlight the many challenges in the official translations (Shiravi, 2004).

2. The Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework to be discussed here looks at the researched views of scholars on translation methods used for the transfer of legal language, the translator’s stance when selecting a relevant method and the issue of equivalence of the main component of the legal language.

The most general view is Wilss (1982) distinction that refers to foreignization and domestication of the TT:

‘The translator can either leave the writer in peace as much as possible or bring

the reader to him, or he can leave the reader in peace as much as possible and

bring the writer to him.’

‘Bringing the reader’ to the ST would require the TT reader to process the translation in its original foreign context, while ‘bringing the writer to the reader’ would mean domesticating the ST in terms of the context familiar to the TT readers and thus making it easy for it to be assimilated by them. In support of foreignizing strategies, Koller (1979) insists that full adaptation is not an accepted method of translation in legal texts as it results in semantic distortion. Nord (2005) further maintains that a TT cannot be regarded as a translation if it is not ‘bound’ to the ST.

Cesana further supports the foreignisation of legal text and proposes the use of neologisms and loan words to render new legal concepts: ‘it is fidelity to the original which counts, not the beauty or elegance of the target language’ (Cesana, 1910: 188, as translated in Šarčević, 2000). Weisflog (1987) who advocates formal equivalence, also known as ‘formal correspondence’, also supports this view.

Tomášek (1990) proposes that legal translation ‘is a procedure based on both linguistic and legal comparative approaches’. He supports the view of that the focus should be the target language, and divides the translation process into ‘intrasemiotic’ and ‘intersemiotic’ (1991). Intrasemiotic translation is the transfer of information from the first to the second semantic level of the SL i.e. transfers from the legal language to the legal metalanguage while intersemiotic translation is the translation of a legal text from the SL to the TL.

In legal translation, many scholars associate legal equivalence with the extent to which the same ‘legal effect’ can be produced in the TT while maintaining fidelity to the ST. This technique, often referred to as a functional equivalence, is described by Newmark (1988) as a procedure that occupies the universal area between the SL and the TL. He also recommends the use of functional equivalence for the purpose of the official translation because it makes the TT both comprehensible to the target reader and faithful to the original ST.

Newmark (1981) further suggests that when dealing with legal documents like contracts that are concurrently valid in the TL, the translator should focus on a communicative approach that is TT-orientated. Vermeer (1982, as translated in Šarčević, 2000) agrees with the view that legal criteria should be taken into account when selecting the most appropriate translation strategy since the meaning of legal texts is determined by the legal context.

According to Šarčević (2000), in official translations the strategies used must above all focus on one main principle, which is fidelity to the source text:

‘Legal translators have traditionally been bound by the principle of fidelity. Convinced that the main goal of legal translation is to reproduce the content of the source text as accurately as possible, both lawyers and linguists agreed that legal texts had to be translated literally. For the sake of preserving the letter of the law, the main guideline for legal translation was fidelity to the source text. Even after legal translators won the right to produce texts in the spirit of the target language, the general guideline remained fidelity to the source text.’

3. The Issue of Equivalence in Legal Translation

At the heart of the aforementioned theoretical framework lies the equivalence of terminology that has its origins in different legal traditions. According to Groot (1998), the first stage in translating legal concepts involves studying the meaning of the source-language legal term to be translated. Then, after having compared the legal systems involved, a term with the same content must be sought in the target-language legal system. Equivalence aims to give the lexis and terminology of two languages equal meaning and corresponding import and significance, and, as can be seen from some of the theoretical stances presented above, it also strives to achieve the same legal effect based on legal interpretation of the source information.

3.1. Functional Equivalence

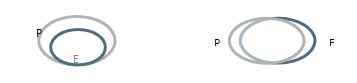

The legal functional equivalent is defined by Šarčević (1988; 1989) as a term in the target legal system designating a concept or institution, the function of which is the same as that in the ST. Weston (1991) further proposes that ‘the technique of using a functional equivalent may be regarded as the ideal method of translation’. According to Šarčević (2000) functional equivalence can be categorised into three groups: near-equivalence, partial equivalence and non-equivalence. These groups are described below and are graphically represented by figures where the Persian legal concept (P) is marked by a grey circle and the English legal concept (E) is marked by a bold circle:

a) Near-equivalence occurs when legal concepts in Persian and English share most of their primary and incidental characteristics or are the same, which is very rare.

Figure 3.1 Near-functional equivalence

One example to illustrate near-functional equivalence is the term ‘contractor’ (ST1). The word ‘contractor’ translated into Persian is ‘Moghatekar’. ‘Moghatekar’ is ‘one of the parties who undertakes a contract’ (Rafiee, 2003), but of a different kind than the permanent employment contract. ‘Moghatekar’ often relates to ‘one – off’ contracts with a set deadline and clearly defined purpose i.e. construction of a building, professional advice and etc. The word has identical connotations in English language: ‘a person who undertakes a contract especially to provide materials, conduct building operations, etc.’ as opposed to an employee who is ‘a person who works under the direction and control of another (the employer) in return for a wage or salary’ (Dictionary of Law, 2003).

Take for example the term ‘common-law wife’ (ST2). The term describes a female cohabiting with a male as his wife without being married to him. On the basis of this description, the term is often translated into Persian legal documents as ‘Sigheh’ (concubine) (Rafiee, 2004). In English common law a ‘common-law wife’ has certain rights and in certain aspects of the law she is recognized as equivalent to a married person i.e. for purposes of protection against domestic violence, for some provisions of the Rent Act or inheritance (Dictionary of Law, 2003). In Persian civil law a ‘Sigheh’ (concubine) has the same legal rights.

Another example that demonstrates near-functional equivalence is the term ‘annual bonus’ in ST3 that is translated into Persian literally as ‘Padasheh Saliyaneh’. However, it has to be highlighted that the term ‘Padasheh Saliyaneh’ is more often referred to in Persian as ‘Eidi’ (New Year’s gratuity or gift, Eskini, 2008). Since the term ‘Eidi’ is unknown in English culture and the meaning of ‘Padasheh Saliyaneh’ is equally clear to a Persian reader, thus the latter can be chosen as a safer but equally adequate option.

b) Partial equivalence occurs when the Persian and English legal concepts are quite similar and the differences can be clarified, e.g. by lexical expansion.

Figure 3.2. Partial functional equivalence

One example that illustrates this type of functional equivalence that calls for attention is

the term ‘director’ (ST1). In Persian director does not have to be a member of the Board of Directors in order to hold that title while in the United Kingdom it is a necessary

Requirement (Eskini, 2008). The role of the subject of the ST is thus that of Financial Director and member of the Board of Directors. To make the reader fully aware of the differences in the responsibilities of a Director or to prompt the reader to seek further legal advice and reassurance that the TT has the same legal effect as the original can be added ‘Ozveh Heiateh Modireh’ (and member of the Board of Directors) in brackets.

The next example belonging to this group of equivalents is the term ‘contract’ (ST2). The Persian concept of ‘contract’ (Gharardad or Aghd) is much broader than its English equivalent as it also incorporates the legal notion of the semi-technical term ‘agreement’ (Rafiee, 2004). The word ‘contract’ (Gharardad) is also an example of the etymological equivalents that often belong to the group of partial functional equivalents. Since in this case the translation was into Persian the term was translated literally, i.e. ‘Aghd’, maintaining its intended English meaning.

Another term ‘Council Tax’ (ST3) is a tax levied on households by local authorities in the United Kingdom.This tax shares many similarities with Persian ‘Avareze Shahrdari’ (Town Tax). Nonetheless, these taxes are calculated slightly differently in Persian and in the United Kingdom and thus, for the purposes of translation, after translating the term as ‘Avareze Shahrdari’ it is necessary to add (Council Tax) in brackets for further clarification.

c) Non-equivalence occurs when only few or none of the important aspects of Persian or English legal concepts coincide or if there is no functional equivalent in the target legal system for a specific ST concept.

Figure 3.3. Non-equivalence

One example that illustrates this type of functional equivalent is ‘a contracting-out certificate’ complemented by additional information ‘under the Pension Schemes Act 1993’ (ST1) that refers to an option given to certain Civil Service employees to contract out of the State Earnings Related Pension Scheme by joining occupational or personal pension schemes in the United Kingdom ( Dictionary of Law, 2003) . The legal concept of the English ‘contracting-out certificate’ does not exist in the Persian legal tradition. For the purpose of the official translation of contracts the legal meaning of this non-equivalent term is most precisely conveyed by the use of a descriptive paraphrase with the original in parenthesis: ‘Gavahiye Dalbar Enseraf Az Tarigheh Tavafogh ’ (Certificate confirming contracting-out by way of agreement (contracting-out certificate). Since the Act it refers to follows the term, it is the target reader’s responsibility to investigate the legal implications regarding the certificate.

Another example of a non-equivalent term is ‘severability’ (ST2). The term does not have a functional equivalent in Persian legal system and none of the latest bilingual or monolingual legal or general dictionaries used in the paper attempts to translate it. The translator must thus first understand the implications of the term in English law and then find a corresponding concept in the TL legal terminology. ‘Severability’ is the title of a contract clause that is intended to condense the meaning of the entire clause and which defines consequences for the entire contract if part of the contract has become impossible to fulfil or is no longer required (Dictionary of Law, 2003). The term must not be translated as ‘Tafkik, Tafkikpaziri’ (separation, divisibility) since then the clause could be interpreted in many ways in a Persian context. Rather, it should be replaced by a neutral paraphrase:‘Tafsire Jodaganehe Az Mofade Gharardad Dar Sorateh Ebtal’ (separate interpretation of the contract provisions in case of annulment) that has the same legal effect as ‘severability’.

Determining the acceptability of functional equivalents is the most important aspect of the process of legal translation and it frequently depends on the context. Šarčević (2000) suggests that when assessing the acceptability of a functional equivalent the legal translator should ‘take account of the structure, classification, scope of application and legal effects of both the functional equivalent and its source term’. Therefore, when dealing with legal conceptual voids or partial equivalents a legal background can be very helpful for the translator. The legal topic must be well researched in order to provide supporting information in the TL.

3.2. Alternative Equivalents and Translating Methods

An important translating rule to be keep in mind when using an alternative equivalent is that the legal translator should uphold the principle of language consistency by using the same equivalent everywhere reference is made to a particular legal concept. Akehurst (in Šarčević, 2000) points out that English courts presume that a difference of terminology implies difference in meaning and thus the use of synonyms is objected to. For example, the Employment Contract defines its subject i.e. Dr Smith, as an ‘employee’ translated into Persian as ‘Karmand’. The term ‘employee’ must therefore be used throughout the document on all occasions when it refers to the subject. Synonyms such as post-holder, job-holder, worker, etc., would suggest that they refer to another person, as would any other corresponding Persian synonyms.

Lawyers agree that from their viewpoint the most effective way of translating legal terms is to use descriptive paraphrases and definitions as these compensate for terminological incongruity by presenting the legal information in neutral language (Šarčević, 2000). This method, however, requires a certain degree of research, legal training and relevant background knowledge on the part of the translator. Lawyers (Šarčević, 2000) also recommend retaining the functional equivalent but followed by the borrowing in parenthesis, with the aim of making it clear that the term derives its meaning from a foreign legal system and thus must be interpreted with reference to the relevant foreign law, i.e., taking the terms already analyzed in point, ‘Council Tax’ should be translated as ‘Avareze Saliyaneh’ (Council Tax).

In a situation where a legal text refers to a specific technical term this lexeme can be used as a borrowing in the TT. Asensio (2003) recommends that borrowings or loan words ‘are necessary when identification is the main concern, as is the case of proper nouns, degrees, grades, etc.’ I do not agree that this recommendation always ensures the most precise alternative equivalent since, for example, the title of doctor, abbreviated as Dr. in Anglo-Saxon countries, is not always equivalent to the title of doctor in Persian due to differences in the educational systems. Since it is not the main aspect of the translation and so there is no more contextual information available, the title has not been altered in the TT. Otherwise, an alternative with annotation would be necessary in order to indicate that the term should be interpreted as part of a foreign system. As put by Šarčević (2000), borrowings without explanation and any naturalisations, modified phonologically or graphologically, derived from them, should be avoided whenever an acceptable equivalent already exists in the target legal system.

3.3. The Translator’s Accountability

Translators who engage in the official translation are subject to legal and sociological factors that condition the way they translate. In the selection of the translating method to be followed for the transfer of legal terminology in official translations, the translator’s stance has a great degree of significance (Asensio, 2003). I disagree with Venuti’s view (2003) that proposes that translators of legal documents are bound by the conditions of their employment in agencies or clients. In accordance with the principle of ideal equivalence where the translator remains ‘nobody in particular’, legal translators should make any endeavor to represent facts in the way they are presented in the ST and not in any other manner requested by a client or based on their ideological preferences, in order to produce a TT of the same legal effect as the original (Belitt, 1978). Translator’s presence might, when necessary, be signalled by those intrusions into the official translations that are indicated by the use of square brackets, and aim at further clarification of conceptual voids in order to ensure accuracy in understanding the exact meaning of the ST by the target reader (Garzone, 2000). Perhaps the need to certify their own works enhances their self-awareness in pursuit of terminological precision. There are laws and codes of ethics written for the monitoring of translation as a profession, regulating the translator’s relations with other translators and with clients. These are imposed by the government (for instance the Persian Ministry of Justice) or by professional translating associations such as the Iranian Association of Official Translators (IAOT) and, in the United Kingdom, the Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIL) and the Institute of Translation and Interpreting (ITI).

Notes

1. The reference abbreviations used throughout this study are as follows: TE (translation equilvance), ST (source text), TT (target text), and TL (target language).

2. For convenience, some of English terms were transliterated into Persian like “Contract” that was transliterated into “Gharardad”.

Works Cited Alcaraz, E. and Hughes, B. (2002). Legal Translation Explained.Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

Asensio, R. M. (2003). Translating Official Documents. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

Belitt, B. (1978). Adam’s Dream: A Preface to Translation. New York: Grove Press.

Chromá, M. (2004). Legal Translation and the Dictionary. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Dictionary of Law (2003). Oxford: OUP.

Eskini, R. (2008). Law of Corporations.Tehran: Rahnama Publications.

Garzone, G. (2000). ‘Legal Translation and Functionalist Approaches: a Contradiction in Terms?’ In ASTTI/ETI (2000), p. 395-414.

Groot, G. R. (1998). ‘Language and Law’. In Netherlands reports to the fifteenth

International Congress of Comparative Law. Antwerp and Groningen: Intersentia,p. 21–32.

Koller, W. (1979). Einfuhrung in die Ubersetyungwissenschft, Hedelberg-Wiesbaden: Qulle und Meyer.

Newmark, P. (1981). Approaches to Translation. New York: Pergamon.

Newmark, P. (1988). A Textbook of Translation. London: Longman.

Nord, C. (2005). Text Analysis in Translation. Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis, Amsterdam/New York, Rodopi.

Rafiee, M. T. (2004). Dictionary of Legal Terms Englih – Persian. Tehran: Majd Publications.

Šarčević, S. (1988). ‘Bilingual and Multilingual Legal Dictionaries: New Standards for

the Future’ in Meta 36, 4: 615–626.

Šarčević, S. (1989). ‘Conceptual Dictionaries for Translation in the Field of Law’ in International Journal of Lexicography 2, 4: 277–293.

Šarčević, S. (2000). New Approach to Legal Translation. London: Kluwer Law International.

Shiravi, A. (2004). Legal Texts (I): Contract Law. Tehran: SMAT Publications.

Tomášek, M. (1990). ‘On selected problems in translation of the legal language.’

Translatologica Pragensia IV, Acta Universitatis Carolinae Philologica 4/1994,

113-120. Prague: Karolinum.

Tomášek, M. (1991). ‘Law – interpretation and translation’. In Translatologica Pragensia V, Acta Universitatis Carolinae Philologica 4-5/1991, 147-157. Prague: Karolinum.

Venuti, L. (2003). The Scandals of Translation. London: Routledge.

Weisflog, W. E. (1987). ‘Problems of Legal Translation’. In Swiss Reports presented at

the XIIth International Congress of Comparative Law. Zürich: Schulthess, p.

179-218.

Weston, M. (1991). An English Reader’s Guide to the French Legal System. Oxford: Berg.

Wilss, W. (1982). The Science of Translation: Problems and Methods. Tübingen: Günther Narr.

زمینه های فعالیت این گروه جهت ترجمه از انگلیسی به فارسی و بالعکس و ساير زبان ها به شرح ذیل می باشد: انواع متون درسی و دانشگاهی،فنی و مهندسی،مدیریتی و صنعتی،حسابداری،اقتصادی و بازرگاني، پزشکی و دندانپزشکی،حقوقی ، قرارداد های بازرگانی بین المللی ، معاهدات سیاسی ، دادخواست ، صورت جلسات شرکت ها ، پایان نامه ، کاتالوگ محصولات و خدمات ، فرآیند های صنعتی ، تولیدی ، پتروشیمی و صنعت نفت ؛ کتاب ها و مقالات کامپیوتر ، نانوفناوری ، بیوتکنولوژی ، فضانوردی ، روانشناسی ، مدیریت ، ادبیات کلاسیک و مدرن ایران و جهان، انواع بروشور ، کاتالوگ ، دفترچه راهنما ، روزنامه ، مجلات و ...

تعداد بازديد : 2654

تاریخ انتشار: جمعه 2 اسفند 1392 ساعت: 16:21