English Translations of the Bible

There are so many translations available today that it can be quite confusing? Which are the best ones? Are some inaccurate? Is "older" always better?" Or maybe "newer" is preferred!

I've tried to summarize twenty-one of the most popular ones below. (There are many others out there.) I've also included some editorial comments from time to time that may point out strengths and weaknesses. I hope this is a help to you. God bless you as you study His Word!

1. Amplified Bible (AMP)

The Amplified Bible was the first Bible project of The Lockman Foundation. It attempts to take both word meaning and context into account in order to accurately translate the original text from one language into another. The Amplified Bible does this through the use of explanatory alternate readings and amplifications to assist the reader in understanding what Scripture really says. Multiple English word equivalents to each key Hebrew and Greek word clarify and amplify meanings that may otherwise have been concealed by the traditional translation method.

2. American Standard Version (ASV)

Published in 1901, the American Standard Version was produced as a revision to the King James Version.

3. Contemporary English Version (CEV)

Uncompromising simplicity marked the American Bible Society’s translation of the Contemporary English Version Bible that was first published in 1995. The text is easily read by grade schoolers, second language readers, and those who prefer the more contemporized form. The CEV is not a paraphrase. It is an accurate and faithful translation of the original manuscripts.

4. Darby Translation (DARBY)

First published in 1890 by John Nelson Darby, an Anglo-Irish Bible teacher associated with the early years of the Plymouth Brethren. Darby also published translations of the Bible in French and German.

5. English Standard Version (ESV)

5. English Standard Version (ESV)

The English Standard Version stands in the classic mainstream of English Bible translations over the past half-millennium. In that stream, faithfulness to the text and vigorous pursuit of accuracy were combined with simplicity, beauty, and dignity of expression. Our goal has been to carry forward this legacy for a new century.

To this end each word and phrase in the ESV has been carefully weighed against the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, to ensure the fullest accuracy and clarity and to avoid under-translating or overlooking any nuance of the original text. The words and phrases themselves grow out of the Tyndale-King James legacy, and most recently out of the RSV, with the 1971 RSV text providing the starting point for our work.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Even though many conservative scholars have found inaccuracies in the orginal RSV, those problems were corrected in the ESV translation. It is one of the best modern translations available today.]

6. Good News Translation (GNT)

The Good News Translation, formerly called the Good News Bible or Today’s English Version was first published as a full Bible in 1976 by the American Bible Society as a “common language” Bible. It is a clear and simple modern translation that is faithful to the original Hebrew, Koine Greek and Aramaic texts. The GNT is a highly-trusted version.

7. Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB)

The Bible is God's inspired word, inerrant in the original manuscripts. It is the only means of knowing God's plan of salvation and His will for our lives. It is the only hope and answer for a rebellious, searching world. Bible translation, both a science and an art, is a bridge that brings God's word from the ancient world to the world today.

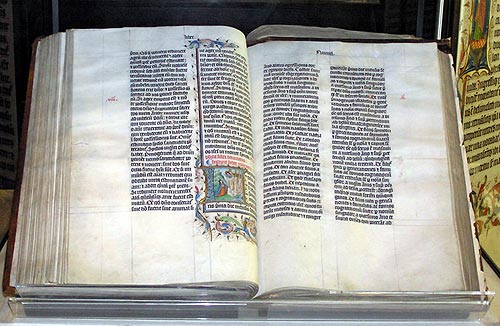

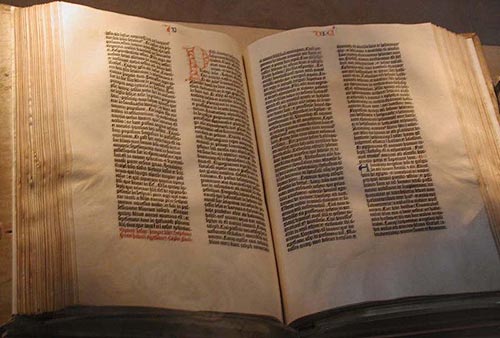

8. King James Version (KJV)

In 1604, King James I of England authorized that a new translation of the Bible into English be started. It was finished in 1611, just 85 years after the first translation of the New Testament into English appeared (Tyndale, 1526). The Authorized Version, or King James Version, quickly became the standard for English-speaking Protestants.

9. 21st Century King James Version (KJ21)

The 21st Century King James Version of the Holy Bible (KJ21®) is an updating of the 1611 King James Version (KJV). It is not a new translation, but a careful updating to eliminate obsolete words by reference to the most complete and definitive modern American dictionary, the Webster's New International Dictionary, Second Edition, unabridged. Spelling, punctuation, and capitalization have also been updated.

What has been historically known as Biblical English has been retained in this updating. It is readily distinguished from the colloquial language of commerce and the media used in contemporary Bible translations.

All language relating to gender and theology in the King James Version remains unchanged from the original.

10. The Message (MSG)

Why was The Message written? The best answer to that question comes from Eugene Peterson himself: "While I was teaching a class on Galatians, I began to realize that the adults in my class weren't feeling the vitality and directness that I sensed as I read and studied the New Testament in its original Greek. Writing straight from the original text, I began to attempt to bring into English the rhythms and idioms of the original language. I knew that the early readers of the New Testament were captured and engaged by these writings and I wanted my congregation to be impacted in the same way. I hoped to bring the New Testament to life for two different types of people: those who hadn't read the Bible because it seemed too distant and irrelevant and those who had read the Bible so much that it had become 'old hat.'"

11. New American Standard Bible (NASB)

While preserving the literal accuracy of the 1901 ASV, the New American Stand Bible has sought to render grammar and terminology in contemporary English. Special attention has been given to the rendering of verb tenses to give the English reader a rendering as close as possible to the sense of the original Greek and Hebrew texts. This translation has earned the reputation of being the most accurate English Bible translation.

12. The NET Bible (NET)

The NET Bible is a completely new translation of the Bible with 60,932 translators’ notes! It was completed by more than 25 scholars – experts in the original biblical languages – who worked directly from the best currently available Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts.

13. New Century Version (NCV)

This translation of God's Word was made from the original Hebrew and Greek languages. The translation team was composed of the World Bible Translation Center and fifty additional, highly qualified and experienced Bible scholars and translators. Some had translation experience on the New International Version, the New American Standard, and the New King James Versions. The third edition of the United Bible Societies' Greek text, the latest edition of Biblia Hebraica and the Septuagint were among texts used.

14. New International Version (NIV)

The New International Version is a translation made by more than one hundred scholars working from the best available Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts. It was conceived in 1965 when, after several years of study by committees from the Christian Reformed Church and the National Association of Evangelicals, a trans-denominational and international group of scholars met at Palos Heights, Illinois, and agreed on the need for a new translation in contemporary English.

15. New International Reader's Version (NIrV)

The New International Reader's Version is a new Bible version based on the New International Version (NIV). The NIV is easy to understand and very clear. More people read the NIV than any other English Bible. We made the NIrV even easier to read and understand. We used the words of the NIV when we could. Sometimes we used shorter words. We explained words that might be hard to understand. We made the sentences shorter.

We did some other things to make the NIrV a helpful Bible version for you. For example, sometimes a Bible verse quotes from another place in the Bible. When that happens, we put the other Bible book's name, chapter and verse right there. We separated each chapter into shorter sections. We gave a title to almost every chapter. Sometimes we even gave a title to the shorter sections. That will help you understand what each chapter or section is all about.

16. New Jerusalem Bible (NJB)

The New Jerusalem Bible is a 1985 revision of the older Jerusalem Bible (JB). The JB was translated from the original languages, but it developed out of a popular French translation done in Jerusalem, which is why it was called the Jerusalem Bible. The NJB, like the JB before it, is known for its literary qualities. While the JB tended to more meaning-based (or functional equivalent), the NJB has moved toward more of a word-based (or formal equivalent) translation.

17. New King James Version (NKJV)

Commissioned in 1975 by Thomas Nelson Publishers, 130 respected Bible scholars, church leaders, and lay Christians worked for seven years to create a completely new, modern translation of Scripture, yet one that would retain the purity and stylistic beauty of the original King James Version. With unyielding faithfulness to the original Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic texts, the translatiors applies the most recent research in archaelology, linguistics, and textual studies.

18. New Living Translation (NLT)

The goal of any Bible translation is to convey the meaning of the ancient Hebrew and Greek texts as accurately as possible to the modern reader. The New Living Translation is based on the most recent scholarship in the theory of translation. The challenge for the translators was to create a text that would make the same impact in the life of modern readers that the original text had for the original readers. In the New Living Translation, this is acََcomplished by translating entire thoughts (rather than just words) into natural, everyday English. The end result is a translation that is easy to read and understand and that accurately communicates the meaning of the original text.

19. New Revised Standard Version (NSRV)

The NRSV translation has been rightly labeled “An Ecumenical Edition,” that has been widely used by both Protestant and Catholic worshippers since 1990.

20. Revised Standard Version (RSV)

َ

Published in 1952, the Revised Standard Version of the Bible is an authorized revision of the American Standard Version. It seeks to preserve all that is best in the English Bible as it has been known and used through the years. It is intended for use in public and private worship, not merely for reading and instruction. [EDITOR'S NOTE: Many conservative scholars have found inaccuracies in the translation work in the RSV.]

21. Today's New International Version (TNIV)

The Today's New International Version is a thoroughly accurate, fully trustworthy Bible text built on the rich heritage of the New International Version (NIV). In fact, this contemporary language version incorporates the continuing work of the Committee on Bible Translation (CBT), the translators of the NIV, since the NIV's last update in 1984.

In translating the NIV, the CBT held to certain goals: that it be an Accurate, Beautiful, Clear, and Dignified translation suitable for public and private reading, teaching, preaching, memorizing, and liturgical use. The translators were united in their commitment to the authority and infallibility of the Bible as God's Word in written form. They agreed that faithful communication of the meaning of the original writers demands frequent modifications in sentence structure (resulting in a "thought-for-thought" translation) and constant regard for the contextual meanings of words.َ

تعداد بازديد : 2443

تاریخ انتشار: یک شنبه 24 آذر 1392 ساعت: 18:13

برچسب ها : tranlation of bible,

Translating Literary Prose: Problems and Solutions

Abstract

This article deals with the problems in translating literary prose and reveals some pertinent solutions and also concentrates on the need to expand the perimeters of Translation Studies. The translation courses offered at many universities in Bangladesh and overseas treat the subject mostly as an outcome of Applied Linguistics. Presently, the teachers and students of translation are confused at the mounting impenetrability of the books and articles that flood the market. Unfortunately, the translators lay more emphasis on the translation of poetry; there should be more research regarding the particular problems of translating literary prose. One explanation of this could be the fact that the status of poetry is considered higher, but it is more possibly due to the notable flawed notion that the novels, essays, fiction etc. possess a simple structure compared to that of a poem and is thus easier to translate. However, many debates have been organised over when to translate, when to apply the close local equivalent, when to invent a new word by translating clearly, and when to copy. Simultaneously, the “untranslatable” cultural-bound words and phrases have been continuously fascinating the prose-translators and translation theorists. The plea made in this article is to admit the fact that there is a lot to be learnt from shaping the criteria for undertaking a prose-translation and we should appreciate the hard work, difficulties, or frustration of the ‘translators’ (go-betweens) in the creation of good sense of the texts.

Keywords: translation, prose, problems, solutions, distant-author, prosaic-ideas, go-between

تعداد بازديد : 4028

تاریخ انتشار: یک شنبه 24 آذر 1392 ساعت: 18:5

Alireza Anushiravani *

Associate Professor of Comparative

Literature

Shiraz University, Iran

Email: anushir@shirazu.ac.ir

Laleh Atashi

Ph.D. Candidate

English Literature

Shiraz University, Iran

Email: laleh.atashi@gmail.com

Abstract

The humanist mission of translation is believed to be rooted in the

universal humane urge to spread knowledge and to eliminate

misunderstanding among people as well as to generate a broader

space for communication. What is absent from this philanthropist

definition is the workings of power and the political agendas that

influence the translator's stance and his/her interpretation of the

text that he/she is translating. The translation of an oriental

literary text by a scholar who is actively involved in the discourse

of colonialism would be an ideologically pregnant text, and a rich

case study for cultural translation. Sir William Jones, an English

philologist and scholar, was particularly known for his

proposition of the existence of a relationship among Indo-

European languages. Jones translated one of Hafez's poems—if

that Shirazi Turk—into English under the title of "A Persian

Song of Hafiz." His Translation denotes a large cultural formation

that emerges through the encounter between the colonizing West

and the colonized East. In this paper, we have examined how

Jones’s Western perspective affects his translation of Hafiz’s

poem and changes its spiritual and mystic core into a secular and

profane love.

Keywords: Hafiz, William Jones, cultural translation, westernization,

orientalism, appropriation

تعداد بازديد : 909

تاریخ انتشار: دو شنبه 20 آبان 1392 ساعت: 21:17

نگاهی بر چهارچوب تحلیلی بازتاب جهان بینی در ترجمه

نگاهی بر چهارچوب تحلیلی بازتاب جهان بینی در ترجمه

و

مصداق های آن در ترجمه های ادبی

محمد غضنفری*

دانشگاه شیراز،

دانشگاه تربیت معلم سبزوار

چکیده

از دیدگاه نظریه پردازان مطالعات ترجمه و ترجمه شناسی، ترجمه فعالیتی است ذهنی، آگاهانه، پیچیده و جهت دار که، به طور کلی، در تمام مراحل آن، تصمیم هایی که مترجم می گیرد، گزینه هایی که انتخاب می کند، و راهکارهایی که در پیش می گیرد، چه بسا همه ی اینها به نحوی متاثر از جهت گیری های ایدئولوژیک او باشد. در این مقاله، مبحث ایدئولوژی در ترجمه و تاثیرات آن بر کار مترجم مورد بررسی و تجزیه و تحلیل قرار گرفته است. نخست، پدیده ی ایدئولوژی و مفاهیم گوناگون آن در زمینه های مختلف مورد بحث قرار گرفته و از دیدگاه زبانشناسی تعریف شده است. سپس، چهارچوبی که از سوی حتیم و میسن (Hatim & Mason) (1990، 1991، 1997) برای ارزیابی و تجزیه و تحلیل ایدئولوژی در متون ترجمه شده پیشنهاد شده است معرفی شده و مقوله هایی که در حیطه ی آن قرار می گیرند – یعنی، گفتمان (discourse)، گفتمانگونه (genre) و متن (text) هر یک جداگانه مورد بحث قرار گرفته، نمونه ترجمه های مربوط به هر یک در جای خود ارایه شده و مورد تجزیه و تحلیل قرار گرفته است.

کلید واژه ها: ایدئولوژی، ترجمه و ایدئولوژی، گفتمان و ترجمه، دستور سامانه ای-کارکردی و ترجمه، ترجمه ی ادبی و ایدئولوژی

* دانشجوی دکتری زبان و ادبیات انگلیسی دانشگاه شیراز و عضو هیات علمی دانشگاه تربیت معلم سبزوار

Abstract

Translation is said to be a conscious, goal-oriented activity. The translator’s decisions, different choices and various strategies in the process of translating are all but a reflection of his/her ideological orientations. Dealing with the issue of ideology in translation, this article examines and analyzes the extent to which translation may affect the ideological output of the original text. First, ideology has been discussed from different perspectives and has finally been defined in terms of linguistics. Then, the framework proposed by Hatim and Mason (1990, 1991, and 1997) to study and analyze ideological aspects of translated texts has been introduced and the constraints in terms of which they have suggested analyzing texts (i.e., discourse, genre, and text) have separately been discussed and, in each case, relevant exemplifications have been presented and properly commented on.

Key words: ideology; ideology and translation; discourse and translation; Systemic-Functional Grammar and translation; literary translation

تعداد بازديد : 2154

تاریخ انتشار: دو شنبه 20 آبان 1392 ساعت: 17:30

Illusion of transparency

The Illusion of Transparency

By Daniel Valles,

a lecturer in Spanish at University College Birmingham

United Kingdom

Introduction

The choices made by the translator during the process of translation are an essential part of producing an adequate target text. They constitute an essential factor in interlingual communication and, effectively, constitute the translator’s voice. However, the search for transparent translations attempts to silence this voice and seems to be clearly linked to the subordinate role translation has traditionally had in the past. This article discusses the concept of the translator’s voice starting with a brief reminder of what translation is and the role played by the translator in this process, together with the influencing factors that are present in any translation. A discussion then follows regarding how the search for transparent translations attempts to silence this voice and the degree to which this is achieved.

A central figure

Before the issue of the voice of the translator can be discussed, it is useful to remember what translation is and the role a translator plays in this process. Hatim and Munday (2004:6) define translation as “the process and the product of transferring a written text from source language (SL) to target language (TL) conducted by a translator in a specific socio-cultural context together with the cognitive, linguistic, cultural and ideological phenomena that are integral to the process and the product”. In a similar way, Lawendoski (cited in Seago 2008:1) sees it as the transfer of “meaning” from one set of language signs to another. Nida (cited in Basnett 2002) explains the process of translation as the decoding of a source text (ST), the transfer of this information and its restructuring in a target text (TT).

In this process, it is the job of the translator to replace “the signs encoding a message with signs of another code, preserving (...) invariant information with respect to a given system of reference" (Ludskanov, cited in Bassnett 2002:25). Newmark (1987) establishes that in the process of decoding and recoding there are a number of factors that need to be taken into account: on the one hand, the style of the writer of the ST, the norms, culture and the framework and tradition of the SL, and on the other hand the reader of the TT, the norms, culture, framework and tradition of the TL. In the middle of these two there is the translator. To this, Nord (cited in Munday 2001) adds the relevance of the role of the translation commissioner, who will give information regarding the intended text functions, the audience, the time and place of text reception, the medium, and the motive for the translation. Nord also emphasizes the role of the ST analysis, which will provide the translator with essential information regarding the subject matter, the contents, assumptions, and composition of text, non-verbal elements, lexic, sentence structure and suprasegmental features. All this information will provide the translator with a number of possibilities as well as constraints when creating the TT, and it is his/her job to transfer the ST into a TT by selecting phrases, sentences and words considering their significance in their particular context and taking into account aspects such as sociocultural environment, genre, field, tenor, mode, etc. (Bassnett 2002).

In some occasions, the changes that a translator needs to make are determined by the linguistic and cultural differences between the SL and the TL over which the translator has no control. In other occasions, adaptation results "from intentional choices made by the translator" (Trosborg 2000:221) in order to produce a more adequate translation. These choices, whether obligatory or optional, is what Hermans (cited in Hatim and Munday 2004:353) calls "the voice" of the translator, that is, the underlying presence of the translator in a TT. O’Sullivan (2003) concurs with this view and argues that this presence is evident in the strategies chosen and in the way a translator is positioned in relation to the translated narrative

Strategies

A few simple examples should illustrate some of the choices and strategies that translators need to make, which confer them a voice in the resulting translation, together with a brief explanation of the process of selecting a particular strategy. In the localization project of a British software license reselling company introducing their services in Spain, which involved the translation of their website and related documentation, the translator decided to keep a number of IT references in English (software, hardware, type of licenses). In translational terms, this would be seen as a foreignizing strategy, or the use of source text loan words in the target text. However, the translator was aware of the acceptance of some of this terminology by the Real Academia Española (the authority in Spanish language matters) and the perceived preference in Spain of English terms in dealing with IT topics. In the translation of the home page, “Are you taking advantage of the current exchange rate?” was rendered as “ Aproveche la actual cotización de la libra esterlina”. This is an example of transposition, where the interrogative sentence was changed into an imperative one, reflecting a more direct style preferred by Spanish speakers. In another section, the webpage referred to software licensing procurement explaining the process of insolvency of British companies, including terms such as insolvency practitioners and case managers. This required the adaptation not only of the specific terminology but also of the process of company insolvencies in Spain in order to successfully communicate the operational issues involved in the procurement of licenses.

Whether or not the translator choices in these examples are the most appropriate may be open to debate, but what is clear is that the strategies employed to produce the TT would not be visible to the target readers unless they had access to the original ST and could understand the SL. Thus, using Hermans’ definition, the voice of the translator could only be heard through the contrastive analysis of both the ST and the TT, that is through the “comparison of the translation with the original and a verification of correspondences, grammatical, lexical and often phonaesthetic" (Newmark 1991:23). This type of analysis would reveal the strategies translators had to develop to produce the translation, the constraints they faced, and the way they worked around those constraints (Lefevere and Bassnett cited in O’Sullivan 2004). An alternative way to hear the voice of a translator and assess the strategies employed would be through the analysis of retranslations of the ST, particularly useful in translation of classic works in different periods in history, which reflect the changes in tastes and norms of the target culture and, therefore, where the presence of the translator becomes apparent (Hatim and Munday 2004). Of course, it can be argued that the translator’s ‘silence’ is simply an illusion, even if it is perfectly acceptable for that to be the case in certain instances.

In other situations, the voice of the translator becomes more prominent, and the reader becomes aware that what s/he is reading is a translation. A clear example of this can be seen in the translation of a Spanish newspaper literary article, where a translator’s note is added under the title of the book Marinero en Tierra. This note explains that “this is a book by the Spanish poet Rafael Alberti (1902-1999) published in 1924. ” In this case, this was an optional choice the translator made, as this information could have been conveyed through, for example, a parenthesis in the main body of the text. Nevertheless, it is evident to the reader that these are the translator’s words and that this information did not appear in the source text.

Venuti (1995) suggests another strategy available to translators that would make them more visible to the reader, foreignization. This consists in adopting a "non-fluent or estranging translation style designed to make visible the presence of the translator by highlighting the foreign identity of the ST” (Venuti cited in Munday 2001:147) and would entail a close adherence to the structure and syntax of the ST, the use of calques and archaic structures, among other things. This approach aims to resist the hegemony of English-language nations and is a reaction to the trend of producing transparent and fluent translations, a concept that is further explored below.

One final situation where a reader is aware of the presence of the translator is bad translations. “Por favor, piense en los próximos pasajeros al utilizarlo” is rendered as “Please, think in the next passengers while using it ”. In this example of reverse translation, it is obvious that the process of recoding suffers from a lack of knowledge of the TL and the reader is well aware that s/he is reading the words of the “translator.”

In all these examples--even in the last one--the purpose behind the selection and application of translation strategies by the translator is to produce a TT that “respects the norms of the target language, that has vis à vis sentence structure, terminology, cohesion of the text and fidelity to the author and his/her intention" (CIOL 2006:16). Venuti (1995), though, goes further and states that nowadays a TT is deemed acceptable by readers, publishers and reviewers when there is an absence of foreign linguistic or stylistic peculiarities and it reads fluently in the TL. The Chartered Institute of Linguists (2006:12) seem to prove this point, as in their criteria for assessing translations “reading like a piece originally written in the target language” is regarded as what translators should aim for when producing a TT. However, Venuti warns us (1995), the more fluent a translation is the more invisible the translator becomes. Schaffner (1999:61) believes that the expectation is that the translator will produce “a faithful reproduction, a reliable duplicate or a quality replica" of the ST that is as good as reading the original, thus rendering the translator “transparent.” This shows a trust in the integrity of the translator and in his/her capability to produce a text that is as good as the real thing and without whom intercultural communication would not be possible (Hermans 1996). Interestingly, however, the expectation also is that a TT is most successful when it is not obvious that it is a translation, requiring the translator not to leave any trace of his work (Schaffner 1999:62). So it could be argued that, on the one hand, the translator is--or should be--regarded as the central piece allowing communication between languages and cultures to take place and that a translation is deemed good when it reads as fluently as if it was written originally in the TL. On the other hand, however, for this to take place it is necessary that the translator stays as invisible and quiet as possible, so that his/her choices and strategies when producing the text are not apparent and the reader is not aware of them. Thus, a translation is good when it does not read like a translation and when it produces the impression of being an original.

Transparency

This seeming paradox is what is called the illusion of transparency (Venuti 1995, Hermans 1996, Seago 2008). Following from the point made above, a transparent translation guarantees integrity, consonance and equivalence and it is as good as the original; this is why people can claim having read Dostoyevsky and Kafka when what they have read in many cases is a translation of their work (Schaffner 1999). The illusion of transparency is based on two premises: that the difference between languages and cultures can be neutralized and that all interpretative possibilities of a text can be summarized or exhausted in one translation (López and Wilkinson 2003). This illusion, Hermans (1996:5) claims, stems from the status that translation and translators have had historically, there having always been a hierarchical difference between originals and translations, between authors and translators, and translation having always been assigned a lower status. And this has been expressed in stereotyped opposites, "creative versus derivative work, primary versus secondary, art versus craft.” This lower status is also evident in the fact that it was not until the middle of the 20th century that translation started to be considered an academic discipline on its own merit (Munday 2001).

Nevertheless, in this apparent illusion, the work of the translator is still very evident as it is he/she who interprets the voices, perspectives and meanings of a ST, intensifying or diminishing certain aspects of it and guiding the reader through the nuances, style, or irony that may be present (Schaffner 1999, O’Sullivan 2003). In the resulting product, the TT, there are always two voices present, the voice of the author of the ST and the voice of the translator (O’Sullivan 2003), and attempting to erase the translator’s intervention actually implies erasing the translation itself (Schaffner 1999). Hermans (cited in Hatim and Munday 2004) concurs with this view and states that it is only the ideology of translation, the illusion of transparency, that blinds us to the presence of the translator’s voice when reading a translation.

Conclusion

From time to time, it is necessary to remind ourselves of what translation is and the crucial role translators have in the process of decoding a ST, analyzing and interpreting it and recoding it in the TL. The production of the TT has a number of influences, starting from the characteristics of the ST and the TT (author/readership, function, register, SL/TL norms, etc.) and the requirements established by the commissioner of the translation (intended text function and readership, medium and motive, etc.). With all this information the translator becomes the central figure that needs to make a number of choices and develop strategies in order to produce an adequate translation. These choices and strategies confer the translator a voice, as all the options the translation has selected will be reflected in the final TT, and this was illustrated through a number of examples. Some of these examples showed how the presence of the translator can sometimes only be perceived through the contrastive analysis of the ST and the TT, thus reducing the volume of that voice. The present trend that assesses translations depending on their fluency and how close they are to reading like an original in the TL produces an interesting paradox: the translator needs to employ strategies and choices (their voice) to create a text that is a reliable and faithful reproduction of the ST but that at the same time does not read like a translation. Moreover, the translator is trusted to interpret a text in the SL and to recode it in the TL but his presence is not welcome in the final text and needs to remain as hidden as possible. This is what authors call the illusion of transparency, the voice of the translator becomes nearly silent, and the reader has the impression that s/he is reading the original or a replica that is as good as. This has its origins in the historical inferior status of translation. But, however fluent and transparent a TT is and however quiet the presence of the translator may seem to be, their voice can never be absolutely silent, since it is the translation itself, with all its lexical choices, grammatical formations, textual structure, that contains the voice of the translator.

List of References

BASNETT, S. (2002) Translation Studies London: Taylor and Francis

BAKER, M. (1992) In other words Oxon:Routledge

CHARTERED INSTITUTE OF LINGUISTS (2006) Diploma in Translation: Handbook and Advice to Candidates London: CIOL

HATIM, B. and MUNDAY, J. (2004) Translation: an advanced resource book. London: Routledge.

HERMANS, T. (1996) Translation’s other London: UCL

LOPEZ, J.L. and WILKINSON, J. (2003) Manual de traducción. Barcelona: Gedisa. Spain.

MUNDAY, J. (2001) Introducing translation studies. London: Routledge

O’SULLIVAN, E. (2003) Narratology meets translation studies, or the voice of the translator in children’s literature. Meta Vol. 48, No 1-2, pps. 197-207

NEWMARK, P. (1987) Manual de traducción. Madrid: Catedra. Spain.

NEWMARK, P. (1991) About Translation Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters

SEAGO, K. (2008) The voice of the translator London: City University London

SCHAFFNER, C. (1999) Translation and norms Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters

TROSBORG, A. (2000) Discourse analysis as part of translation training. Current issues in language and society. Vol. 7, No 3, pps. 205-228.

VENUTI, L. (1995) The translator’s invisibility New York: Taylor and Francis

تعداد بازديد : 1768

تاریخ انتشار: پنج شنبه 11 مهر 1392 ساعت: 8:52

برچسب ها : illusion of transparency,

ترجمه های دانشجویی

چنانچه که میدانیم برقراری ارتباط و انتقال دانش دو حوزه اصلی و کاربردی ترجمه محسوب میشوند. در زمینه انتقال دانش جدای از حوزه نشر و رسانه، دانشگاه نیز بشکل گستردهای با ترجمه سرو کار داشته و بدان نیازمند است. از اینرو بخش قابل توجهی از حوزه ترجمه به ترجمههایی که اصطلاحاً آن را ترجمه دانشجویی نامیدهاند اختصاص یافته است. میتوان گفت تقریباً همه مترجمین کار ترجمه را با انجام ترجمههای دانشجویی آغاز میکنند و جز عدهی اندکی که بخت یارشان بوده و جذب شرکت یا سازمان بزرگی شدهاند بقیه مترجمین کم و بیش سر و کارشان به ترجمههای دانشجویی میافتد و بیشتر از سر ناچاری چنین ترجمههایی را میپذیرند. اما این مدل ترجمه دانشجویی چیست و اصلاً چرا به وجود آمده است؟ ریشهاش کجاست و چه مسایلی حول آن وجود دارد؟ در این مقاله نگاهی ویژه به ترجمه دانشجویی و تبعات آن در حوزه ترجمه و حرفه مترجمی خواهیم انداخت.

در نگاه اول کندوکاو در ترجمههای دانشجویی و برخورد نقادانه با آن خصوصا از سوی یک مترجم بیمورد و چه بسا اشتباه به نظر برسد. ممکن است مترجمین بسیاری مخالف چنین پرداختی به این مسأله باشند چراکه هرچه باشد یکی از منابع درآمد مترجمین محسوب میشود. اما اگر دقیق شویم و پیامدهای آن را دنبال کنیم خواهیم دید آنچه که ترجمه دانشجویی نامیده میشود از جهات مختلف نه تنها به حوزه ترجمه و حرفه مترجمی بلکه به انتقال دانش و دانشجویان ما لطمههای بسیاری زده است.

در بیشتر موارد ماجرای ترجمه دانشجویی از اینجا آغاز میشود که استادی برای دریافت نمره پروژه به دانشجویانش ترجمه – تقریبا ده صفحه – از کتاب یا مقالهای را پیشنهاد میکند. بیشتر دانشجویان نیز که از عهده ترجمه متن برنمیآیند – حتی آنانی که دانش زبانی خوبی دارند کار برگردانی و ترجمه را سخت یافته و زمان مورد نیاز برای انجام آن را ندارند – به سراغ مراکز ارائه دهنده خدمات ترجمه رفته یا خود مترجمی پیدا میکنند تا در ازای مبلغی ترجمه متن را برایشان انجام بدهد. میتوان گفت کمتر از یک درصد ترجمههای دانشجویی توسط خود دانشجویان انجام میشود. این موضوع را همه و خصوصا استادان دانشگاه میدانند و مسئلهای نیست که کسی آنرا منکر شود. یعنی به عبارت دیگر در دانشگاههای ما به روشنی – البته نه بطور مستقیم در این مورد – با پول نمره خریده میشود. این اساسیترین مشکل به اصطلاح ترجمههای دانشجویی است. دانشجو بدون کوچکترین زحمتی متن ترجمه شده را به ازای مبلغی در حدود سی تا پنجاه هزار تومن از مترجمی گرفته و به دست استادش میرساند و نمره مورد نظر آن را دریافت میکند. متأسفانه نه تنها پروژههای ترجمه بلکه تقریباً تمامی پروژههای دوره دانشجویی، از پاورپوینت گرفته تا پایان نامه را میتوان به دکانهایی که انجام چنین کارهایی را به در و دیوار خود زدهاند سپرد و در ازای مبلغی خیال خود را از انجام آنان راحت کرد. امروزه دیگر دانش کسب نمیشود، خرید و فروش میشود. حال اینکه چرا چنین مسئلهای نه بصورت پنهانی بلکه کاملاً آشکارا و حتی قانونی در کشور ما انجام میگیرد را دیگر باید از مسئولین مربوطه جویا شد.

از زاویه دیگری اگر به موضوع نگاه کنیم به این سؤال بسیار مهم میرسیم که چرا استادان دانشگاهی به دانشجویان خود که نه درسشان ترجمه است و نه سررشتهای در ترجمه دارند پروژه ترجمه میدهند. با پیگیری موضوع درمییابیم که بیشتر این ترجمهها برای استادان دانشگاهی منافع شخصی دربردارد: مقالاتی را که مرتبط با مدرک دکترایشان است یا اینکه جزو منابع مقاله یا کتابی است که در دست تهیه دارند یا اینکه صرفاً مطلبی چشمشان را گرفته و بد نمیبینند آنرا بخوانند برای ترجمه به دانشجویان خود میسپارند. هرازگاهی هم به فکر چاپ کتابی به نام خود بعنوان مترجم یا مؤلف میافتند و برای انجام آن کتاب را (بصورت مساوی و عادلانه البته) بین دانشجویان خود تقسیم میکنند تا ترجمه آن را در ازای نمره برایشان بیاورند. در ترجمه دانشجویی، دانشی منتقل نمیشود، دانشجو مطلبی یاد نگرفته و نفعی نمیبرد. این دومین مشکل قابل توجه در مسئله ترجمههای دانشجویی است.

حال نوبت این است که بپرسیم آیا افراد موجود در چرخه ترجمه دانشجویی از اینکار راضی هستند؟ پاسخ به ظاهر مثبت است. مترجم در این میان پولی بدست میآورد، دانشجو به راحتی نمرهای کسب میکند و استاد نیز به رایگان صاحب ترجمهای میشود. اما اینکار چندان رضایت هر کدام از طرفین معامله را جلب نمیکند. هزینه پرداختی برای ترجمههای دانشجویی بسیار کمتر از ترجمههای معمول بازار است. مترجمین تقریباً با نصف قیمت مجبور اند ترجمههای دانشجویی را بپذیرد و همین دریافت اندک پول باعث میشود که در کار خود سهلانگار بوده و ترجمه مناسبی ارائه نکنند. متأسفانه همین روش و رویکرد ترجمه کردن غیر اصولی و غیر متعهدانه به مرور زمان در ناخودآگاه مترجم نهادینه شده و باعث میشود کیفیت ترجمههایش هیچگاه به حد عالی و بینقص نرسد. کیفیت پایین و پر اشکال ترجمه نیز طبعا خوشایند دانشجویان نیفتاده و بیشتر اوقات آنان را از اینکار پشیمان میکند. استادان نیز به ترجمه روان و مورد نظر خود نرسیده و با متنی رو به رو میشوند که در بهترین حالت به بازبینی و ویرایش نیاز دارد که از حوصله یا جیب استادان فراتر است. بدین شکل حجم اصلی ترجمههای دانشجویی در نهایت روانه سطل زباله شده و هیچ بازدهی به همراه ندارند. این نیز یکی دیگر از معضلات اساسی ترجمههای دانشجویی است که هزینه و انرژیهای صرف شده بسیار برای آن باعث انتقال دانشی نشده و عملا به هدر میروند.

از طرف دیگر چون این آثار در هیچ کجا جمعآوری یا حتی ثبت نمیشوند احتمال اینکه یک متن واحد بارها و بارها توسط اشخاص مختلف ترجمه یا ارائه شود بسیار است. همین خلاء اطلاعاتی باعث شده که عدهای سودجو نیز بازار سیاهی برای ترجمههای دانشجویی به وجود بیاورند. با یک جستجوی ساده در اینترنت میتوان سایتهای مختلفی را یافت که ترجمههای دانشجویی آمادهای را برای فروش گذاشتهاند. ناگفته پیداست که این واسطهها بدون اطلاع مترجم این متون (که نام و نشانی ساده نیز بر روی اثر ترجمه خود ندارند) و حتی سفارشدهنده نخستین آنها مبادرت به فروش اینگونه ترجمهها کرده و هیچ مبلغی از این فروشها به جیب صاحبان اصلی آنها نمیرسد.

چنانچه عنوان شد ترجمههای دانشجویی از زوایای چندی چون خریدن نمره آن، هزینه پایین و کیفیت نامطلوب این نوع ترجمهها، عدم داشتن کارایی و مهجور ماندن حجم اصلی آنها، کاستن دقت مترجمین در فن ترجمه و ملکه ذهن شدن عادات غلطی در ترجمه کردن و... دارای اشکالات اساسی بوده و فاقد بازدهی کارا و موثر برای جامعه است. تغییر رویکرد و نگاه به این حوزه میتواند قدم بسیار مثبتی در انتقال دانش و کسب اطلاعات علمی بیشتر محسوب شود. برای نیل به این مهم اقدامات و طرحهای اصلاحی خاصی میتوان انجام داد که در مقاله جداگانهای به چند مورد از آنها اشاره خواهیم کرد.

نویسنده: کاوان بشیری

تعداد بازديد : 2012

تاریخ انتشار: جمعه 3 مهر 1392 ساعت: 19:5

برچسب ها : ترجمه دانشجویی,

The Art of Poetry and Its Translation

By Mariam Hovhannisyan,

Yerevan State University, Romance and Germanic Philology Faculty,

Student Scientific Society

Supervisor, PhD professor Seda Gabrielyan

“Poetry must be translated by a poet”

Eghishe Charents

Abstract

According to Oxford English Dictionary poetry is “The art or work of poet”. Another depiction of it is given by John Ruskin in his “Lectures on Art” (1870), “What is poetry? The suggestion, by the imagination, of noble grounds for the noble emotions”. According to T. S. Eliot “Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality”. Percy Bysshe Shelly describes poetry as the eternal truth. “A poem is the very image of life expressed in its eternal truth”. And at last according to Robert Frost “The figure a poem makes: it begins in delight and ends in wisdom”. This must know any translator so as to acknowledge the real virtue of the work he deals with. Translation is very often referred to be as an art. So the task of a translator is to make an art from art keeping the aesthetic value of the work. Robert Frost once described poetry as “what gets lost in translation”. He meant, of course, that it is impossible to carry over from one language into another the special qualities of a poem-its sound and rhythm, its meter syntax and connotations. Some critics have felt that in translating poems “translators betray them, inevitably turning the translation into something which at best may approximate, but which invariably distorts, the original”[1]. This point of view, however, has not prevented translators from continuing their difficult, but important work.

Translation of poetry is one of the most difficult and challenging tasks for every translator. Returning to Robert Frost’s definition, according to which “Poetry is what gets lost in translation”, we can say, that this statement could be considered as a truthful one to a certain extent because there is no one-to-one equivalent when comparing two languages. Even if the translators possess a profound knowledge in the source language they would not be able to create a replica of the original text.

In the theory of Translation Studies there are different approaches to the problems in this sphere of translation. Among the outstanding translators and translation theorists John Dryden in his article “The Tree Types of Translation” spoke about the verbal copier of a poem, who “is encumbered with so many difficulties at once”, that he cannot get out of it. Describing verbal translation of a poem as something impossible he mentions, that the translators are “to consider, at the same type, the thought of his author, and his words, and to find out the counterpart to each in another language” being confined to the compass of numbers, and the slavery of rhyme. He approaches the claim of the Armenian prominent writer and translator, Eghishe Charents who is sure that a poem is to be translated by a poet. John Dryden writes about this “No man is capable of translating poetry besides a genius to that art”. He also adds, that the translator of poetry is to be the master of both of his author’s language and of his own.*

Another theorist in TS, Friedrich Schleiermacher, highlights the importance of the sound in poetry as one of the major problems in translation and defines poetry as a work, ”where a most excellent and indeed higher meaning resides in the musical elements of language as they are manifested in rhythm”. According to him “whatever seems to have an impact on sound qualities and the fine-tuning of feeling and thus on the mimetic and musical accompaniment of speech- all this will have to be rendered by our translator”.*

American poet, critic and translator Ezra Pound whose experience in poetry translations goes far beyond theory, believes that much depends on the translator. “He can show where the treasure lies, he can guide the reader in choice of what tongue is to be studied…”. He calls this as an “interpretive translator” of poetry. Parallel to it he offers “other sort” of translation, “where the translator is definitely making a new poem”*. Thus there are two types of poetry translation, one which directly renders the thought of the author, and the second, which is based on the original, but transfuses some new spirit. Admittedly, if the translator succeeds in rendering both the form and the content, the translation is considered to be a successful one. This point of view has been sphere of investigation for Eugin Nida, professional linguist and Bible translator. He underlines the difference between prose and poetry highlighting the importance of form. “Only rarely can one reproduce both content and form in a translation, and hence in general the form is usually sacrificed for the sake of the content”. The translator of poetry aims at producing “on his reader an impression similar or nearly similar to that produced by the original”.* In fact “every poem is a poem within a poem; the poem of the idea and the poem of words” (Wallance Stevens). Without idea words are empty, without words idea is empty. The translator is to avoid of the emptiness.

Roman Jakobson writes in his article “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation” about the possibility and impossibility of translation and defines poetry as “by definition untranslatable. Only creative transposition is possible”.

To sum up the theoretical approaches of the above mentioned people, it is admittedly clear, that poetry is the most difficult type of text and can be considered to be untranslatable. But if we have the vivid examples of successful translations of poetry, we can never claim that it is untranslatable. They also touched the problems like the freedom of the translator, which in our opinion is to be confronted. We can never refer to a rendering as a translation if it is just an original-based work. It must be close to the original as much as possible. This all can be reflected in the following diagram (1).

The diagram is in state of Y=X, where X stands for the translation, Y for the quality of the translation. The line a stands for the translation process which shares the right angle into two equal parts (45°) denoting that during his translation process the translator pays equal attention to the quality of his work and the idea of the original, trying not to go beyond the author’s words. The point O depicts the original work and the best and most successful translation. The two points coinside, because they are one and the same work in different languages. If the translation is far from O for 1 unit, then the quality of the translation reduces to 1 unit. Correspondingly if the translation goes far for 2 units, the quality reduces to 2, etc. To put poetry translation and its quality in a rough way, we use this materialistic and vivid way to depict it. But this does not give the idea what a translator should do. In reality, what should be preserved when translating poetry are the emotions, the invisible message of the poet, the uniqueness of the style in order to be reached the same effect in the target language as it is in the source. When talking about the translation of poetry we could not but mention some of the numerous problems encountered during this process.

Firstly, we would like to draw the attention to the form of a poem. This is probably the first thing that the reader notices before reading. The translator should try to be as closer to the original as he/she can. For example, if haiku has to be translated, the short meaningful and condensed form should be preserved, because an author chooses deliberately the form and the structure of the poem as an inseparable part of the overall message that should be transferred and sensed by the readers. Thus for instance sonnet (fourteen lines) cannot turn into a villanelle (five three-line tercets and a final four-line quatrain), or an elegy (a lament for the dead) into an ode (devoted to the praise or celebration). Types of poetry are also important. It is necessary for the translator to understand whether he/she deals with a narrative or a lyric poetry. Because the difference between them is huge. Narrative poems stress story and action, and lyric poems stress emotion and song.

The second matter to discuss is the shape of a poem. A pictogram is visually concrete and has special shape. For example Lewis Carrol’s “The mouse’s tale” taken from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” is translated into Armenian with a shape of a tale of a mouse. And here the choice of the translator is commendable. The shape of poetry is also in its stanzas. The translator can invert the stanzaic form of a poem during the translation if it is not compulsory to keep. But it is better to translate from the couplet (a pair of linked verses) into a couplet, from a tercet (three successive lines bound by rhyme) into a tercet, from quatrain (a stanza of four lines) into a quatrain, from a quintain (a five line stanza) into a quintain, and from sestets (a six-line stanza) into a sestets, etc. (septet, octet, Spenserian, seven-, eight- and nin-line stanzas respectively)[2].

The third range of problems that occur while translating poetry are the nuances of word’s meaning. The translator can be confused in two ways. On the one hand he/she can find difficulties in understanding which from the numerous meanings of the word the author has used. On the other hand, he/she can be puzzled which equivalent from the target language to use. Emily Dickinson writes;

A word is dead

When it is said,

Some day.

I say it just

Begins to live

That day.

So the words must be under close examination of a translator. It is important to find out whether the word is used in its denotative, dictionary meaning or its connotative meaning, “which is the associated meanings that have built up around the word, or what the word connotes”[3]. Through the effects of the words the authors use in their poems they make an imagery. Poems include such details which trigger our memories, stimulate our feelings, and command our response. The ideas in poetry are important, but the real value of a poem consists in the words that work their magic by allowing us to approach a poem is similar to Francis’s “Catch” implies: expect to be surprised; stay on our toes; and concentrate on the delivery. This all is done by the words. Sometimes their meaning goes even far and reaches to the creation of some stylistic effects. Among them the most typical for poetry is metaphor. “It is metaphor, saying one thing and meaning another, saying one thing in terms of another, the pleasure of ulteriority. Poetry is simply made of metaphor”(Robert Frost, ”The Constant Symbol”). Another stylistic figures include hyperbole or exaggeration, synecdoche or using part to signify the whole, metonomy or substituting an attribute of a thing for the thing itself, personification, endowing inanimate objects or abstract concepts with animate characteristics or qualities, etc*.

The problems accuring in the process of translation may be concerned with the different elements of poetry. We can learn to interpret, appreciate and translate poems by understanding their basic elements. The elements of a poem include a speaker whose voice we hear in it; its diction or selection of words, its syntax or order of those words; its imagery or details of sight, sound, taste, smell, and touch; its figurative language or nonliteral ways of expressing one thing in terms of another, such as symbol and metaphor; its sound effects, especially rhyme, assonance, and alliteration; its rhythm and meter or the pattern of accents we hear in the poem’s words, phrases, lines, and sentences, and its structure or formal pattern of organization.

We would like to discuss another matter causing a lot of problems in translating poetry, which is the grammatical difference between the languages. The grammatical rules compulsory for the prose are not obligatory for the poems or we could just say that the poets do not follow them strictly wherefore the translators are usually puzzled over such very creative works. Sometimes, the poets in their imaginativeness offer really unusual, striking, new and surprising works, which are difficult for translation. The translator should be combinative in order to transfer this novelty, hidden sense or specific grammatical structure. So as to clarify the situation we can pay attention to the second person pronoun and its usage. This transition in styles should be preserved in the target language because it carries the whole emotional and psychological world of a poet. For instance, the word “you” is sometimes difficult to translate. It can either be “¹áõ” or ”¸áõù”. In this case the translator must catch the intension of the author. Of course the grammatical shifts are possible in poetry translation, because here the translator aims at transmitting more the content. So any choice of the translator to change the grammatical form can be justified until it spoils the meaning.

Poetry has always been closely related to music. It “is an art of rhythm but is not primarily an effective means of communication like music”[4]. It, as well as being something that we see, is also something that we hear. “There remains even now a vibrant tradition of poetry being delivered orally or “recited”; and even the silent reading of poetry, if properly performed, should allow the lines to register on the mind’s ear.”[5]

When speaking about the sound the first thing to mention is rhyme, which can be defined as the matching of final vowel or consonant sounds in two or more words. Thouth there are unrhymed poems, they give in in the point of view of their sound value. Robert Frost, who wrote traditional rhymed styles, growled that writing without rhyme is like “playing tennis with the net down”. It is a little strict, because many rhymed lines look and sound better in an unrhymed shape. In fact, sound is anything connected with sound cultivation including rhyme, rhythm, which refers the regular recurrence of the accent or stress in a poem, assonance or the repetition of vowel sounds, onomatopoeia, which implies that the word is made up to describe the sound, alliteration or the repetition of the same sounding letters, etc. A translator must try to maintain them in the translation. As Newmark (1981: 67) states, "In a significant text, semantic truth is cardinal [meaning is not more or less important, it is important!], whilst of the three aesthetic factors, sound (e.g. alliteration or rhyme) is likely to recede in importance -- rhyme is perhaps the most likely factor to "give" -- rhyming is difficult and artificial enough in one language, reproducing line is sometimes doubly so." In short, if the translation is faced with the condition where he should sacrifice one of the three factors, structure, metaphor, and sound, he should sacrifice the sound.

On the other hand, the translator should balance where the beauty of a poem really lies. If the beauty lies more on the sounds rather than on the meaning (semantic), the translator cannot ignore the sound factor.

The fourth thing that can cause problems in translation is the cultural differences. I would like again to refer to Osers’s article “Some Aspects of the Translation of Poetry”. A profound knowledge is necessary for the translation of idioms and phrases too, which are a product of the specific traditions and mentality in one’s country. Words or expressions that contain culturally-bound word(s) create certain problems. The socio-cultural problems exist in the phrases, clauses, or sentences containing word(s) related to the four major cultural categories, namely: ideas, behavior, product, and ecology (Said, 1994: 39). The "ideas" includes belief, values, and institution; "behavior" includes customs or habits, "products" includes art, music, and artifacts, and "ecology" includes flora, fauna, plains, winds, and weather.

In translating culturally-bound expressions, like in other expressions, a translator may apply one or some of the procedures: Literal translation, transference, naturalization, cultural equivalent, functional equivalent, description equivalent, classifier, componential analysis, deletion, couplets, note, addition, glosses, reduction, and synonymy. In literal translation, a translator does unit-to-unit translation. The translation unit may range from word to larger units such as phrase or clause.

He applies ’transference procedure’ if he converts the SL word directly into TL word by adjusting the alphabets (writing system) only. The result is ’loan word’. When he does not only adjust the alphabets, but also adjust it into the normal pronunciation of TL word, he applies naturalization.

In addition, the translator may find the cultural equivalent word of the SL or, if he cannot find one, neutralize or generalize the SL word to result ’functional equivalents’. When he modifies the SL word with description of form in the TL, the result is description equivalent. Sometimes a translator provides a generic or general or superordinate term for a TL word and the result in the TL is called classifier. And when he just supplies the near TL equivalent for the SL word, he uses synonymy.

In componential analysis procedure, the translator splits up a lexical unit into its sense components, often one-to-two, one-to-three, or -more translation. Moreover, a translator sometimes adds some information, whether he puts it in a bracket or in other clause or even footnote, or even deletes unimportant SL words in the translation to smooth the result for the reader.

These different procedures may be used at the same time. Such a procedure is called couplets. (For further discussion and examples of the procedures, see Said (1994: 25 - 28) and compare it with Newmark (1981: 30-32)).

The writer does not assert that one procedure is superior to the others. It depends on the situation. Considering the aesthetic and expressive functions a poem is carrying, a translator should try to find the cultural equivalent or the nearest equivalent (synonym) first before trying the other procedures.

The global context is also important. It includes the system of conditions under which the author has written, to whom the poem is directed or dedicated, and makes the author’s psychological situation explicit for the translator. If the poem contains a hidden irony towards somebody, than a translation must have it as well. Buy this of course depends on the content of its value.

Summarizing all these problems which are just a small part from the obstacles that the translators should overcome we realize how hard and difficult is the process of translation and how gifted, creative and knowledgeable should the translator be.

And he should have the same inspiration as the author has had when writing. As Plato states “the poet is the light and whinged holy thing, and there is no invention in him until he has been inspired and is out of his senses, and reason is no longer in him…”[6]. The translator of a poem must equate the author, the artist and be inspirated from the poem. There are lots of translations of poetry which are not successful. The reason is: “nobody else can alive for you; nor can you be alive for anybody else. There is the artist’s responsibility and the most awful responsibility on earth. If you can take it, take it- and be. If you can’t, cheer up and go about other peaple’s business…” (e.e. cummings “Six Nonlectures” on the responsibility of art).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. “English Teaching FORUM”, volume 47, number 1, 2009.

2. “English Teaching FORUM”, volume 40, number 2, April 2002.

3. “English Teaching FORUM”, volume 41, number 3, July 2003.

4. John Dryden, 1680, The Three Types of Translation, in Translation Studies Reader, ed. by S. Gabrielyan, Yerevan: Sahak Partev, 2007.

5. Friedrich Shleiermacher,1813, On the Different Methods of Translating, in Translation Studies Reader, ed. by S. Gabrielyan, Yerevan: Sahak Partev, 2007.

6. Roman Jakobson, 1969, On the Linguistic Aspects of Translation, in Translation Studies Reader, ed. by S. Gabrielyan, Yerevan: Sahak Partev, 2007.

7. Eugene Nida, 1969, Principles of Correspondence, in Translation Studies Reader, ed. by S. Gabrielyan, Yerevan: Sahak Partev, 2007.

8. Ezra Pound, Guido’s Relations, 1969 in Translation Studies Reader, ed. by S. Gabrielyan, Yerevan: Sahak Partev, 2007.

9. Bene¢t’s Reader’s Encyclopedia, Harper Collins Publishers, third edition.

10. Ann Charters, Samuel Charters, Literature and Its Writers, An introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, University of Connecticut, Second edition.

11. Czeslaw Milosz, “The Witness of Poetry”, Harvard University press, London, 1983.

12. John Strachan and Richard Terry, Poetry, An introduction, New York University Press, 2000.

13. Robert DiYanni, Literature: Reading Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, 5th edition, 2002.

14. Plato, “Poetry and inspiration” (translated by Benjamin Jowett), in Literature: Reading Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, ed. by Robert DiYanni, 2002.

15. Michael Meyer, The Bedford Introduction to Literature, University of Connecticut, Boston, third edition.

16. The Princeton Handbook of Multicultural Poetries, ed. by T.V.F.Brogan, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1996.

17. Petya Georgieva, ASPECTS OF POETRY TRANSLATION, www.nbu.bg/PUBLIC/IMAGES

18. SOME POSSIBLE PROBLEMS IN TRANSLATING A POEM, http://www.translationdirectory.com/article640.htm.

[1] Robert DiYanni, Literature: Reading Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, 5th edition, 2002, page 771

* See Seda Gabrielyan, “The Translation Studies Reader”, 2007, pages 53-54

* See also page 91

* See also pages 126-130

* See also pages 161-167

[2]John Strachan and Richard Terry, Poetry, An introduction, New York University Press, 2000, pages 25-47

[3] Ann Charters, Samuel Charters, Literature and Its Writers, An introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, University of Connecticut, Second edition, page 837

* See Robert DiYanni, Literature: Reading Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, 5th edition, 2002, page 709-755

[4] Czeslaw Milosz, “The Witness of Poetry”, Harvard University press, London, 1983, page 25

[5] John Strachan and Richard Terry, Poetry, An introduction, New York University Press, 2000, page 49

[6] Plato, “Poetry and inspiration” (translated by Benjamin Jowett)

تعداد بازديد : 2653

تاریخ انتشار: پنج شنبه 11 شهريور 1392 ساعت: 9:21